History: Where Brown Trout Came From: The History of a Transplanted Icon

- The Fly Box LLC

- Jul 2, 2025

- 3 min read

How a European native became a mainstay in American fly fishing and why it's still not considered "native."

Origins: Brown Trout in Europe

Brown trout (Salmo trutta) have been swimming in European rivers for thousands of years. Native to a wide range of waters from the British Isles to the Balkans, these fish evolved in cold, clear, and well-oxygenated streams. In places like Germany, Scotland, and Norway, they became cultural staples—valued as both food and sport.

But their story didn’t stay in Europe.

The First Transplants: Brown Trout Come to America

In the late 1800s, American fisheries managers and anglers were hungry for sportfish that could thrive in a wider range of waters. Native brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) were already beloved in the East, but they struggled in warmer or degraded streams, especially as deforestation and pollution increased.

In 1883, the U.S. Fish Commission received brown trout eggs from Germany—specifically from the Black Forest region. These eggs were hatched and stocked in Michigan's Baldwin River, part of the Pere Marquette River system. The hatchery attempt was one of several in the 1880s and 1890s, and while some early introductions failed, others took hold.

Soon, brown trout were stocked across the East Coast, Midwest, and eventually into Western rivers. Their adaptability made them ideal for the changing landscape of American waters.

The Spread: From East to West

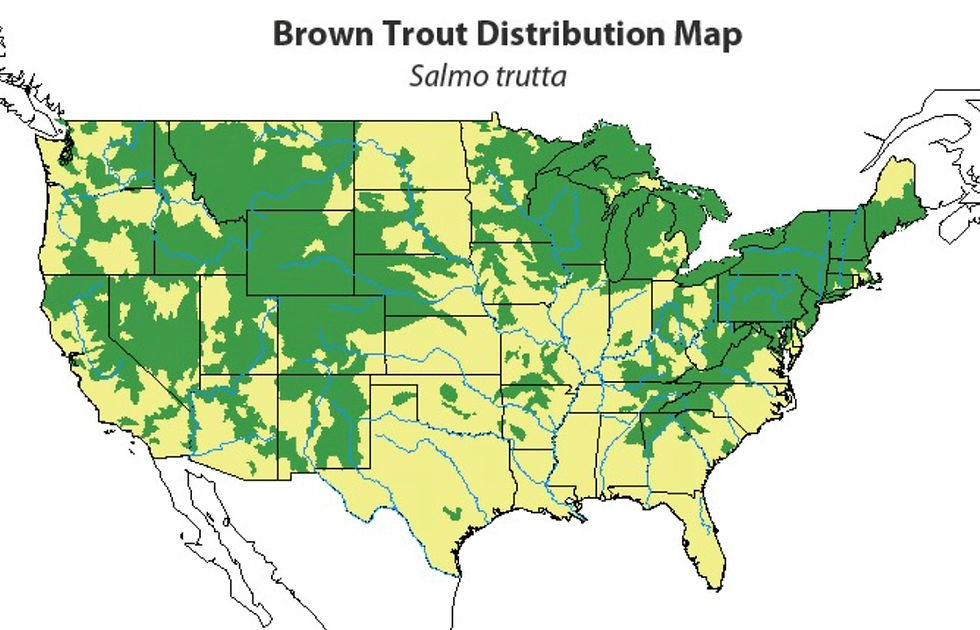

Though they were first introduced to rivers in the East, brown trout were never considered fully native to North America. But they spread fast:

Northeast & Midwest: Stocking programs proliferated in New York, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

Rocky Mountains & West: States like Montana, Colorado, and Utah began stocking them in high-country streams and tailwaters by the early 1900s.

California: By the early 20th century, they reached West Coast fisheries, though rainbow trout remained dominant there.

Their success had to do with resilience: browns could tolerate warmer water, outcompete native fish in some systems, and even thrive in slightly polluted or modified environments.

So Why Aren’t They Considered Native?

Some anglers wonder whether brown trout, having reproduced in the wild for over a century, might now be considered native. But in ecological terms, nativity is not based on how many generations a species has been present. Instead, it depends on whether the species arrived without human intervention. Even a population of brown trout that has existed for dozens of generations in a single river system is still classified as non-native because it was introduced by humans, not nature. In contrast, "wild" simply means the fish were born in the stream—not hatchery-raised—regardless of species origin.

Here’s how the breakdown typically works:

Native: Originated in the region naturally, without human interference.

Non-native (or introduced): Brought by humans, intentionally or not, but not necessarily harmful.

Invasive: A non-native species that causes ecological harm.

Brown trout usually fall into the middle category. They're not invasive in every setting, but in some waters, they do outcompete or hybridize with native trout species like brook trout or cutthroat trout.

Why Fly Fishers Love (and Debate) Brown Trout

Fly fishers often prize brown trout for their size, selectivity, and wariness. They’re considered more challenging than rainbows, and more adaptable than brook trout. A big wild brown—especially one born, not stocked—is a trophy in nearly any water.

But they’re also controversial:

In Western states, brown trout have displaced native cutthroat trout in some systems.

In some conservation circles, brown trout are seen as an obstacle to native fish restoration.

However, in many Eastern and Midwestern waters, they fill a void left by declining native species.

Final Cast

Brown trout might not be native to the U.S.—but they’re part of our fly fishing story now. Their history is a mix of science, sport, and shifting ecosystems. Understanding where they came from—and what they’ve meant to fisheries across the country—is key to understanding both the legacy and future of American fly fishing.

Comments