Remembering the Edmund Fitzgerald & A Look Into The History of Fly Fishing on Lake Superior

- The Fly Box LLC

- Nov 10, 2025

- 5 min read

This Free Feature is Brought to You by Casts That Care

Casts That Care is the daily fly-fishing charity news published by The Fly Box LLC, sharing real stories, conservation updates, and community features that give back to the waters we love.

If you enjoy this piece, you can read over 300+ more articles (with new ones published every day) and subscribe here. Each month, we donate 50% of all subscriptions to a different fly-fishing charity.

November 10, 1975. The SS Edmund Fitzgerald vanished beneath the freezing waters of Lake Superior, taking all 29 crew members with her. The loss was a chilling reminder of the lake’s power and unpredictability. Fifty years later, that same body of water remains a place of awe and respect for another group of people who have long been drawn to its edges: fly anglers.

Today, on the 50th anniversary of the Fitzgerald’s sinking, we look back at how fly fishing culture on Lake Superior has evolved over the last half-century and where it stands now.

The Early Days: Cold Waters and Rugged Anglers

Lake Superior has always been a working lake. In the early 1900s, the shoreline was dominated by fur traders, commercial fishermen, and shipping ports. The cold-water species that defined its ecosystem, lake trout, brook trout, and the now-iconic steelhead, were the backbone of both sustenance and sport.

By the 1940s, a few adventurous anglers began exploring Superior’s vast shoreline and tributaries with fly rods, chasing coaster brook trout and early steelhead runs. It wasn’t easy. Roads were rough, maps were unreliable, and the weather could change in an instant. But that challenge built a kind of angler that still defines the region today: resilient, resourceful, and deeply respectful of the lake.

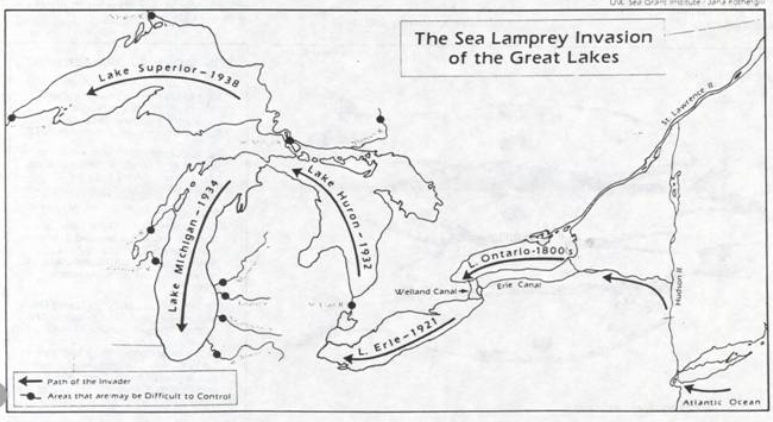

During the 1950s and 60s, Superior’s fish populations suffered. Sea lamprey invasions decimated lake trout, and industrial pollution damaged many tributaries. Recreational fly fishing was a niche pursuit then, practiced mostly by locals who knew the rivers by heart. When the Edmund Fitzgerald sank in 1975, fly fishing was still in its infancy around the lake—more a passion for a small circle of diehards than a cultural movement.

The Rebirth of a Fishery

The decades that followed saw massive recovery efforts. The Great Lakes Fishery Commission implemented lamprey control programs, while state and provincial agencies began restocking lake trout and rehabilitating tributaries. The result was the rebirth of one of North America’s most resilient cold-water fisheries.

By the 1990s, fly anglers from across the country were traveling to the North Shore of Minnesota, Wisconsin’s Bayfield Peninsula, and Ontario’s rugged coastline to experience steelhead and coaster brook trout runs. Conservation and access improved, and new fly shops appeared in Duluth, Marquette, and Thunder Bay.

Fly fishing here became less about numbers and more about the story—the weathered sandstone cliffs, the fog lifting off the lake, and the feeling of casting into something that could turn violent in minutes. It was fly fishing on the edge of wilderness, and it attracted the kind of people who sought meaning as much as fish.

Today’s Fly Fishing Culture on Lake Superior

From the lake’s vast cold expanse flow hundreds of tributaries, each with its own fly-fishing character. The Brule River in Wisconsin, sometimes called the “River of Presidents,” is famed for its steelhead runs and brown trout.

Minnesota’s North Shore holds more than 60 short, fast rivers that pour into Superior, from the Pigeon near Canada down to the Lester at Duluth—rivers that come alive with spring and fall steelhead. In Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, rivers like the Huron, the Two-Hearted, and the Ontonagon wind through forests and rock canyons, offering some of the most scenic fly-fishing in the Midwest. Across the border, Ontario’s Nipigon River system is legendary for its giant brook trout, descendants of the same strain that once held the world record.

These rivers shape how anglers approach Lake Superior. Fly fishing here is built around the seasons—swinging streamers for spring steelhead, skating dries for summer brookies, and stripping large baitfish patterns for lake-run browns in fall. Because of the lake’s size and cold, the fish follow temperature and flow changes closely, and success depends on reading both the river and the forecast. Each tributary offers a different rhythm, from technical pocket-water fishing to broad estuary swings where the river meets the lake. The variety of water, combined with the raw environment, keeps anglers returning year after year.

Fifty years after the Fitzgerald, Lake Superior has become a unique fly-fishing destination. Anglers target wild steelhead, brook trout, salmon, and lake-run browns. Tributaries like the Brule, Nipigon, and Pigeon River are now legendary in fly-fishing.

The modern scene combines tradition and innovation with lightweight switch rods, cold-water fly lines, and synthetic materials adapting to Superior’s harsh conditions. Conservation is key: catch and release is common, invasive species are monitored, and habitat restoration is ongoing.

Fly fishing on Superior remains challenging. Winds can reach 30 knots, waves can rise like walls, and calm waters can become dangerous quickly. This unpredictability is part of its appeal, reminding anglers they are at the mercy of a greater force.

A Living Legacy

The story of fly fishing on Lake Superior is one of survival and respect. The same power that took down the Edmund Fitzgerald is the same power that shapes the lake’s currents, its weather, and its spirit. To fly fish here is to engage with that force—to cast into something wild, unpredictable, and deeply alive.

Fifty years later, the lake stands as both a memorial and a living ecosystem, where each swing of a fly is a quiet act of gratitude for those who came before. From the rugged tributaries to the open water, fly anglers continue to write their own chapters in the ongoing story of Superior.

This Free Feature is Brought to You by Casts That Care

Casts That Care is the daily fly-fishing charity news published by The Fly Box LLC, sharing real stories, conservation updates, and community features that give back to the waters we love.

If you enjoy this piece, you can read over 300+ more articles (with new ones published every day) and subscribe here. Each month, we donate 50% of all subscriptions to a different fly-fishing charity.

Comments